Designing Trust: Four Perspectives on Human-Centered AI

Fan Na, Yile Zhang, Sijing (Clair) Sun, and Helen Tsui

Fan Na, Yi-le Zhang, Sijing (Clair) Sun, and Helen Tsui are product and AI designers working across fintech, enterprise AI, cloud infrastructure, and financial services. Their combined experience spans global brands such as Amazon, AWS, and Bank of America, with strengths in human-computer interaction, research, and scalable systems. Together, they bring a shared interest in building AI-powered products that feel clear, reliable, and meaningfully aligned with real human needs.

Fan Na: I’ve always been a designer with roots in digital and graphic design. Over the years, I’ve built my career as a senior product designer specializing in the fintech space, leading design across both agency and in-house teams. My work has spanned global brands as well as complex enterprise platforms. Beyond work, I run my own creative brand, where I keep exploring how design connects people visually and emotionally.

Yile Zhang: I’m Yi-le, a UX and product designer specializing in AI-driven, human-centered experiences. I’ve led design for complex enterprise AI products at companies like Amazon and C3 AI, helping organizations turn technologies into tools people actually trust and use. Outside of enterprise work, I am also leading multiple HCI academic research projects and designing passion projects like Kumo. My ultimate focus is on bridging cutting-edge technology with the real psychological needs of this generation.

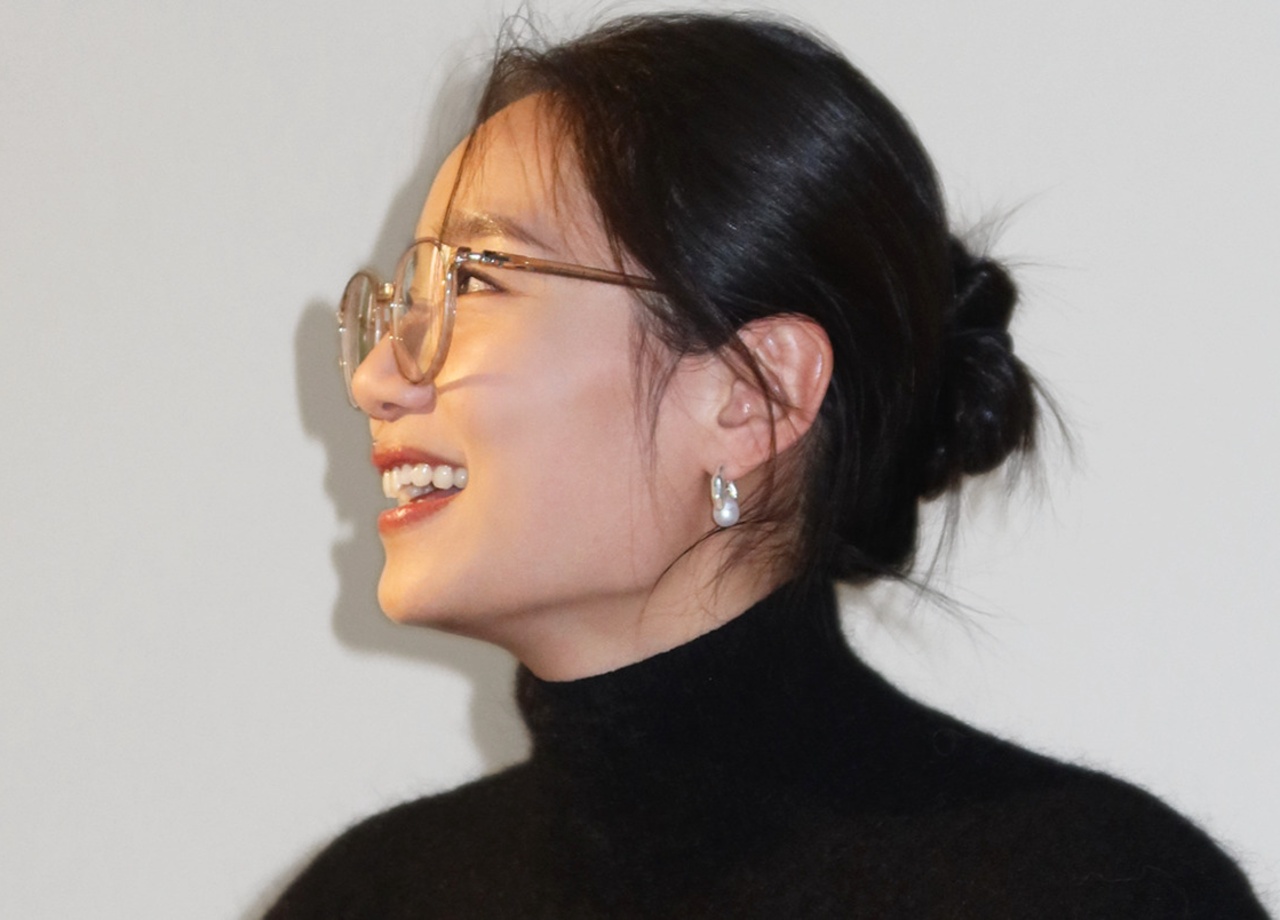

Sijing (Clair) Sun: I am a Senior AI Designer at Amazon Web Services, working on generative and agentic AI for the Amazon Quick Suite. My background in Human Computer Interaction shaped how I translate complex systems into clear, human centered experiences, and that foundation ultimately led me to pursue design as a career. I am especially drawn to designing AI that feels understandable, collaborative, and trustworthy. Outside AWS, I co author AIverse.design, a pattern library used by many teams, and sharing knowledge through writing and teaching keeps me inspired and continually pushes my creative thinking.

Helen Tsui: I'm Helen, a Senior Product Designer at Bank of America. My design work spans both B2B and B2C spaces, reaching users from teenage users who are starting personal financing, to operations-managing small business owners. Outside of work, I love creative expressions through tangible mediums like photography and pottery. My background in human-computer interaction and psychology, combined with emerging opportunities in AI and personal health/wellness, inspired my team and me to explore the project of Kumo: designing an AI companion for personal well-being and longitudinal growth.

Yile Zhang: Being recognized by the NY Product Design Awards is meaningful to me in two ways. On a personal level, it feels like a validation of my craft — the years I’ve invested in honing my design skills. On a product level, it’s also a validation of Kumo as an idea: that there *is* value in building mental health tools that are both emotionally sensitive and technologically forward-looking. I’ve always believed that good design should bridge technological progress and human needs.

Kumo is exactly about that: using the latest advances in generative AI, but shaping them through careful, humane design to support a new generation’s psychological needs. This recognition gives me more confidence to keep pushing for products where design and technology grow together, and where innovation in AI is always grounded in empathy, ethics, and real human stories.

Sijing (Clair) Sun: Being recognized in the NY Product Design Awards feels both refreshing and motivating. In a big tech environment where the pace is fast and the focus is often on delivery, this recognition gives me space to stretch creatively and explore ideas beyond the day to day. As someone deeply invested in AI, it also lets me express my own point of view on how these technologies should be designed for real people. It feels like a meaningful confirmation that my growth, perspective, and design approach are moving in the right direction, and it motivates me to keep experimenting and raising the quality of my craft.

Helen Tsui: I am also motivated and grateful for this recognition. Kumo started out as a passion project outside my day-to-day work, a space where I could explore the intersection of AI with my personal interests in psychology and human behavior. Winning this award validates the exploration and transforms what began as a creative experiment into something with real potential. It's incredibly fulfilling to see this work celebrated, and it's given me the momentum and confidence to expand Kumo further and bring it to life as a fully realized product.

Sijing (Clair) Sun: This achievement has encouraged me to stay inventive and curious in my own practice, reminding me to keep pushing for ideas that feel original and meaningful. It also created a strong point of proof for KUMO, showing that the concept and design approach resonate beyond my immediate circle. That recognition gives KUMO a solid foundation for future product ideas and opens the door for deeper exploration, collaboration, and potential growth.

Yile Zhang: Kumo started as a passion project for me. But being recognized for it made me realize that when we actually put our ideas into the world, they can matter much more than we initially expect. For my own career, this achievement has given me the confidence to pursue bolder ideas and to experiment without being so afraid of failure. It’s a reminder that thoughtful, human-centered concepts can resonate beyond our immediate circle.

For our team, this award is a strong concept validation for Kumo. It tells us we’re heading in a meaningful direction, so we’re now more committed to refining the product, stress-testing the design, and eventually developing it into something real that people can use in their everyday emotional lives.

Experimentation is at the heart of our process. Prototypes, user interviews, even small copy changes are all experiments to reveal what people actually need, not just what we imagine they need.

With Kumo, experimentation completely changed the direction of the product. Our first concept was very focused on "immediate help": an AI chat that could respond 24/7 to emotional questions and make mental support more accessible. On paper, it sounded like a strong solution to what we heard in research — that many people can’t easily access therapy or professional support.

But as we experimented, talked to domain experts, and tested early flows with users, we realized something deeper. People didn’t realized that what they want is not answers or “someone to talk to,” but it is to have power to support themselves, from the darkest to every moment in their lives.

Those learnings led us to pivot Kumo from a pure “instant support” tool into a long-term growth companion: focusing on structured reflections, insight cards after each conversation, and a visual “growth map” of themes in their life. That shift only happened because we were willing to question our initial assumptions, run experiments, and let real feedback reshape the product.

For us, one of the most unusual yet powerful sources of inspiration is video games. We were especially drawn to how games design engagement loops, visual worlds, and subtle storytelling affect experiences. With Kumo, we were very inspired by the game Monument Valley. It’s not just the beautiful isometric visuals; it’s the calm, contemplative mood and the way the game guides you without over-explaining anything.

We borrowed that philosophy for Kumo’s experience: instead of loud gamification, we use gentle motion, simple shapes, and a sense of “quiet progression” to help users feel safe and reflective. It might sound unusual to treat a mental health product like a game world, but thinking in terms of level design, atmosphere, and micro-interactions helped us create an experience that feels less like “using a tool” and more like entering a calm, supportive space.

Fan Na: People often see the final design as something effortless, but behind it are countless rounds of iteration and internal refinement. A single interface might go through multiple Waterfall & Design thinking process, where every detail is carefully considered. Good design is never accidental.

Yile Zhang: I wish more people understood that design isn’t just about “making things look nice” at the end — it’s a way of thinking and a way of expressing how we see the world. For me, design is how I express my own point of view *and* how I make sense of complex problems on behalf of others. A lot of the work happens before pixels: listening to people, sitting with their emotions, testing different ideas, and being willing to throw things away when they don’t quite feel right. Good design is not a straight line from question to solution. It’s a continuous conversation between technology, constraints, and human needs, and the final UI is really just the visible tip of a much deeper process.

Sijing (Clair) Sun: I wish more people understood that meaningful design starts with a strong grasp of both human needs and the technology behind the experience. Even though design is often seen as a non technical role, understanding AI and the systems that power a product helps designers create solutions that are realistic, reliable, and genuinely helpful. At the same time, great design is never just about responding to a request. It comes from looking past what people say they want and uncovering the real problems in their lives. When you combine technical understanding with that kind of curiosity and empathy, the design process becomes far more powerful and leads to solutions that truly matter.

Helen Tsui: Throughout this project, I was constantly reminded of the 'fail fast' principle. In a 0-to-1 product like Kumo, there are countless directions and ideas we can explore. As a team of four designers, we committed to rapid iterations — quickly testing concepts, learning from failures, refining our ideas, and moving forward. This foundational product development principle became the cornerstone of our design process.

With Kumo, we didn’t have a traditional client, but we did feel the pull of “what looks right in the market.” At the beginning, we also fell into a common assumption: if AI chat can answer people’s emotional questions 24/7, then that must be a good mental health product. Our early research highlighted “inaccessibility of mental support” as a big pain point, so it was very tempting to just build an always-available AI listener and stop there.

The turning point was when we broke the problem back down to first principles and asked *why* people wanted more accessible support in the first place. Through that lens, what they really longed for wasn’t just instant answers, but a stronger sense of their own mental agency: understanding themselves better, making sense of what’s happening, and feeling more capable of handling future challenges.

That’s where the balance comes in. We still respect the “market expectations” of convenience and responsiveness, but we don’t let them define the core. Instead of optimizing only for quick replies and chat volume, we designed Kumo around deeper, slower outcomes: helping people build insight, emotional vocabulary, and inner strength over time.

So my way of navigating that tension is: listen to external expectations as useful noise, but always come back to first principles and the long-term impact on the person using the product.

One big challenge was identifying the “real” underlying needs behind people’s emotional struggles, instead of just creating “another mental health app” on top of the latest AI trend. We surveyed 100+ young adults to learn how they process stress, identity, and relationships. And we conducted rounds after rounds user validation sessions to define Kumo not as a generic chatbot, but as a growth companion.

A second challenge was finding the right balance between what AI should do and what should be left to human psychological support. We were very conscious about ethics: Kumo isn’t meant to replace therapy or crisis care. So we designed clear boundaries for the AI, focused on gentle reframing and reflection, and made sure the tone, prompts, and flows encourage self-awareness rather than dependency or overpromising what technology can do.

On a more practical level, all of us had full-time jobs, so time and collaboration were tight. We overcame that by being very intentional about scope, dividing responsibilities clearly, and working in focused, async bursts. Looking back, those constraints actually forced us to sharpen the concept and communicate it more clearly.

Helen Tsui: Creative blocks often require me to pause for a bit and draw inspiration through different approaches. Sometimes it's browsing comparative or competitive design patterns to see how others have tackled similar challenges. Other times, it's conversations with creative minds across disciplines—fresh perspectives can unlock new ways of thinking. But most often, I find inspiration in other mediums entirely, like museums and galleries. While these spaces aren't the same medium as my everyday work, they reignite my creative energy and make me want to pick up my pen and return to the drawing board.

Sijing (Clair) Sun: When I hit a creative block, I recharge by immersing myself in the latest products, technologies, and industry shifts. Staying close to what is emerging helps me sharpen my instincts and, in many ways, separates a good designer from someone who is continuously pushing toward expertise. This habit is also why I co authored AIverse.design. It gives me a space to study real examples, learn from competitive patterns, and capture the insights in a way I can return to later or share with others. That constant exposure to new ideas and well crafted solutions keeps my creativity active and continually evolving.

Yile Zhang: When I hit a creative block, I usually step away from the problem and do something completely unrelated to design. Sometimes I listen to podcasts about neuroscience or biology, sometimes it’s mystery or mythology stories, and other times I just go for a run and let my mind wander. These activities seem unrelated on the surface, but they often give me fresh perspectives.

A sentence from a podcast, a metaphor from a story, or even the rhythm of running can suddenly connect with something I’m working on. A lot of my ideas come from these “crossovers” between different disciplines and past knowledge, rather than forcing myself to push pixels when my mind feels stuck.

Fan Na: My interest in mental health comes from a personal place. I’ve experienced periods when I wasn’t in a great mental state and that made me deeply interested in how design can support emotional well-being. One of my core values is humility. I’ve seen how easy it is for people including myself to believe we’re always right. But as designers, I think we need to stay humble to accept that our ideas aren’t always the best, and great design comes from collaboration, dialogue, and even disagreement. We’re all part of a shared process where every thought, good or bad, helps shape the final solution for the people we design for.

Yile Zhang: At the core, I design with two values in mind: being deeply human-centered and using technology with intention. I don’t just want products to be “smart”; I want them to be understandable, and genuinely supportive and empowering for the people who use them. A lot of this comes from my background in neuro-psychology and human behavior, where I learned how complex—but also how beautiful—our thoughts and emotions can be.

Later, working inside big tech companies that are driving AI and other emerging technologies, I saw both sides: how powerful these tools are, and how alienating they can feel when they’re not translated well for people outside the tech world. Bringing those two worlds together shaped my belief that good design and good technology must remain fundamentally human-first. For me, that means creating products that don’t just showcase what technology can do, but help people make sense of their world, feel emotionally supported, and use these tools in ways that are aligned with their own needs and values.

Sijing (Clair) Sun: Years of designing in AI have shown me how powerful the technology can be when applied with care, and that understanding motivates me to create solutions that genuinely help people in practical, everyday ways. Because of that, I value usefulness and clarity more than aesthetics. I also care about building experiences that feel truly resonant. With Kumo, for example, we iterated many times to move beyond a simple chat flow and shaped an immersive island based experience where growth is visual, playful, and long term. The entire Kumo islands concept and its light gamification follow this core value of making design feel meaningful, relatable, and grounded in real human progress.

Helen Tsui: I believe in the power of designing for empathy and designing for good. They are essential to creating ethical, sustainable systems that genuinely benefit people. I guide my design with intention through a human-centered lens, and consider a simple design decision could have lasting impact. I ask myself: Could this inadvertently create biases in human behavior? Could it generate false impressions or unintended consequences? This critical awareness can be especially important when working with AI and personal wellness, and ensures that I'm not just solving for functionality, but rather designing responsibly for long-term wellbeing for people.

Our biggest advice is: don’t start by chasing awards or “perfect” visuals, start by caring deeply about a real problem and real people. If you stay close to genuine human needs, your work will naturally stand out more than if you only focus on trends or aesthetics.

Second, don’t wait until something feels “big enough” or “perfect” before you put it into the world. Kumo started as a small passion project. It only turned into something meaningful once we wrote it down, prototyped it, and shared it. You learn so much by shipping, getting feedback, and iterating in public.

Finally, keep your curiosity alive outside of design. Read things that have nothing to do with UI, listen to people’s stories, learn how other fields think. Over time, that mix of curiosity, empathy, and craft will give you your own point of view, and that’s what really makes a designer successful and sustainable in the long run.

We would love to work with Naoto Fukasawa, an iconic Japanese designer we've admired for a long time. With his field of expertise in furniture and industrial design, we’d love to collaborate with him to see how his philosophy of Unconscious Design — the approach of creating affordance, “almost invisible interactions” in physical objects — could be applied in digital experiences. He would offer unique insights into ways to bridge tangible and digital dimensions that we have probably not fully explored yet.

Our answer is: we want people to feel a bit more seen, a bit less alone, and a bit more in control of their own story.

With Kumo, for example, of course we care about tasks like “capture an insight” or “complete a reflection,” but underneath that, we care more about someone exhaling and thinking, “Okay, this makes sense now,” or “Maybe I’m not as stuck as I thought.” If the product can help someone make sense of what they’re going through and leave them with a little more clarity and agency, then we feel the design is doing its real job.

Winning Entry

Click here to read Slow Moments, Big Ideas: Inside Yuanqing Yao’s Observed Design World.

ADVERTISEMENT

IAA GLOBAL AWARDS

MUSE Awards

Vega Awards

NYX Awards

TITAN Awards

- TITAN Business Awards

- TITAN American Business Awards

- TITAN Property Awards

- TITAN Women In Business Awards

- TITAN Health Awards

- TITAN Innovation Awards

- TITAN Brand Awards