Biao Cao Explores Urban Texture Through Campus Design

Biao Cao

Biao Cao is an architectural designer based in Los Angeles. He entered the field through an unconventional path, teaching himself architectural skills through practice before formal training, and was driven by a deep curiosity about people, culture, and space.Thank you so much. My name is Biao Cao, and I am an architectural designer based in Los Angeles. My path into design has been unconventional, but it’s also what shaped who I am today. I didn’t study architecture during my undergraduate years—instead, I entered the profession first.

My passion for design was strong enough that I taught myself architectural skills, applied to firms, and eventually received an opportunity from a Chinese architect who saw potential in me. That experience opened the door to architecture and strengthened my belief that this was the career I truly wanted.

What inspired me most to pursue design is my curiosity about the world—people, culture, space, and the way environments shape our experiences. I’ve always loved observing how things work, how spaces influence emotions, and how ideas can be transformed into physical form. Even as a child, I loved making things with my hands. Design felt like the natural place where all of these interests come together.

Later, I continued my journey at SCI-Arc, where I formally studied architecture for the first time. The experience deepened my understanding of design as both a technical discipline and a form of artistic expression. For me, architecture is not just about buildings—it’s a medium for thinking, questioning, and storytelling. That blend of creativity, craft, and critical thinking is what inspires me to pursue design every day.

Being recognized by the MUSE Design Awards means a great deal to me. It is not only an honor, but also a meaningful affirmation of the long and unconventional path I’ve taken as a designer. My journey into architecture has never been straightforward—I entered the profession before receiving formal training, taught myself many of the skills I needed, and worked incredibly hard to catch up with others who had years of academic background.

This award feels like a validation of that persistence. It reminds me that passion, dedication, and curiosity can open doors, even when the road is difficult. It also reflects the support I have received from mentors and people who believed in me along the way.

On a personal level, the recognition encourages me to keep exploring, questioning, and pushing my work further. On a professional level, it strengthens my belief that design is a powerful way to communicate ideas and create meaningful experiences.

To have my work recognized on an international stage is both humbling and motivating—it inspires me to continue growing as a designer and to keep contributing to the broader design community.

This achievement has had a meaningful impact on my career and on the teams I’ve been part of. For me personally, being recognized by the MUSE Design Awards has strengthened my confidence as a designer and validated the effort I’ve put into growing within the profession. It has also helped bring more visibility to my work within the architectural community, which is valuable when collaborating with new teams or presenting ideas internally.

For the firms and teams I’ve worked with, the award has brought a sense of pride as well. Many colleagues and mentors who supported me throughout my journey felt encouraged to see the work being recognized on an international stage. It reflects not only my contribution, but also the collective environment that helped me grow.

In terms of opportunities, the recognition has opened doors to more conversations—both within the industry and across creative fields. It has sparked interest from architects, designers, and artists who are curious about my work, and it has expanded my professional network. This exposure has given me more chances to join interesting projects, collaborate with diverse teams, and continue developing my design perspective.

Overall, the award has motivated me to keep improving, to stay curious, and to take on projects that challenge and inspire me.

Experimentation plays a central role in my creative process. Because I entered architecture through observation and self-learning, I naturally treat design as a space for testing ideas, questioning assumptions, and discovering new possibilities. I rarely arrive at a final concept immediately—my process usually involves exploring multiple variations, making quick physical models, sketching iterations, and studying how small changes can shift the entire experience of a space.

I also believe that experimentation is not just about form—it’s about understanding how light, material, proportion, and narrative interact. Often, I learn the most when an experiment doesn’t work as expected, because it reveals something I couldn’t have anticipated.

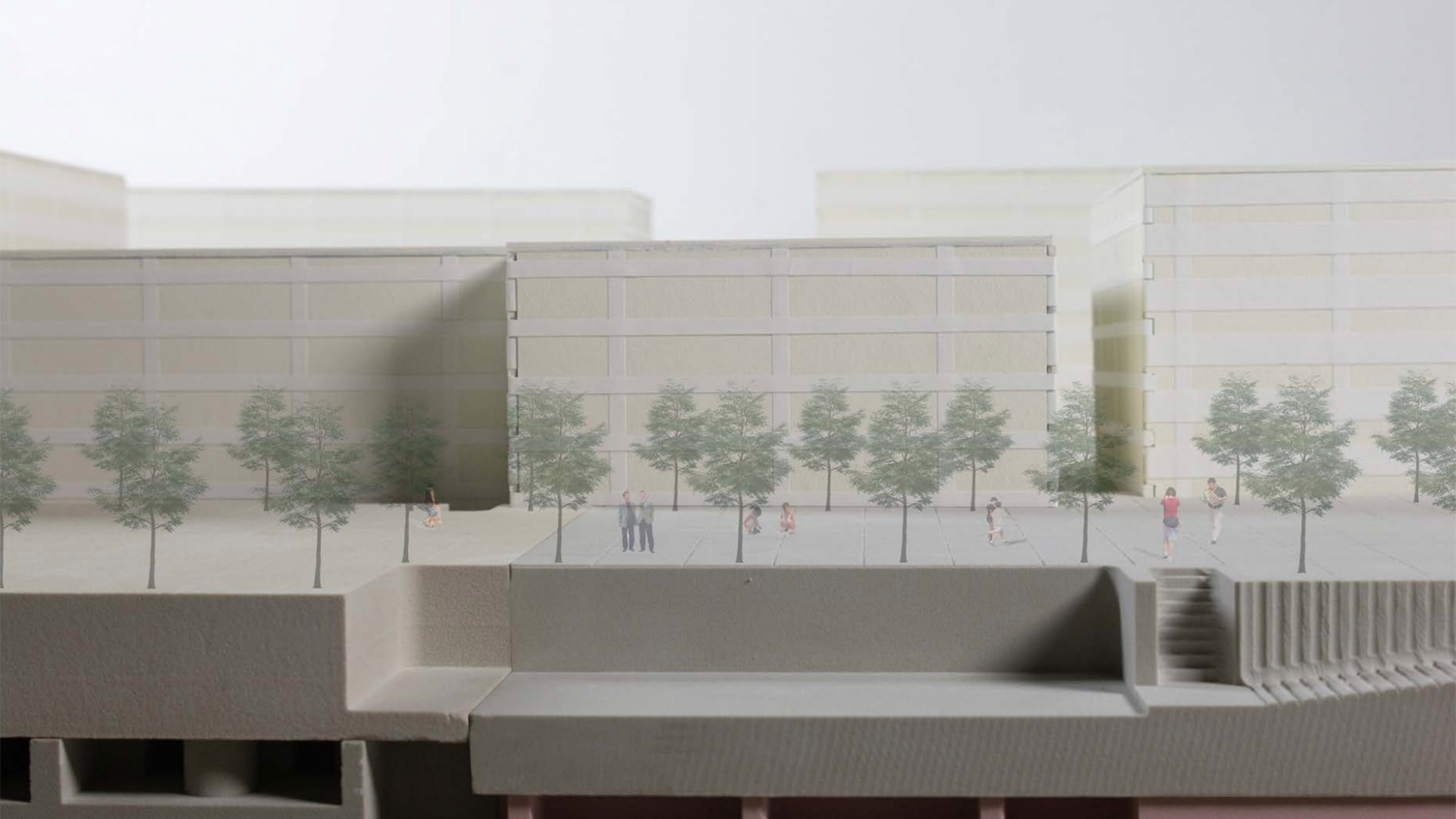

My graduate thesis project at SCI-Arc, which later became the work recognized by the MUSE Design Awards, is the best example of this. During the early stages, I experimented heavily with physical model-making and material studies. Instead of relying only on digital tools, I built dozens of small handmade models to test spatial qualities, structural logic, and the emotional tone of the project.

Each iteration taught me something different—how a slight shift in geometry could change circulation, how transparency and opacity affected perception, or how shadows could create a completely new reading of the form. These experiments ultimately shaped the final direction of the thesis and helped me build a project that felt both thoughtful and expressive.

For me, experimentation is not a separate phase of the design process—it is the design process. It’s how I think, how I learn, and how I push my work forward.

One of the most unusual sources of inspiration I’ve ever drawn from came from something very ordinary—shadows, textures, and light patterns I observed during my daily walks. While working on my thesis project, I became fascinated not only by the shifting geometries created by sunlight, but also by the subtle textures of surfaces and how they transformed throughout the day.

These changes—soft in the morning, sharp and elongated in the afternoon, diffused at sunset—revealed spatial qualities that were unplanned yet incredibly poetic.

I began photographing these moments, especially on film, and studying the textures, rhythms, and shadow compositions they created. I found that these observations were more than visual impressions—they were natural diagrams shaped by light, material, and time.

I started extracting these elements and transforming them into a new design language. Sometimes it became the basis for a building façade; other times it informed a larger urban texture or circulation pattern. I love exploring how these elements behave at different scales, and how the same geometry, when expanded or reduced, produces entirely different spatial experiences.

This experimentation became a major part of my thesis, which later won the MUSE Design Award. I translated these shadow and texture studies into physical models and design iterations, exploring how light could define space rather than simply illuminate it. It taught me that meaningful inspiration often comes from quiet, overlooked moments in everyday life. The world constantly draws its own patterns—we just have to pay attention and let them guide our imagination.

One thing I wish more people understood about the design process is that it is not linear. Great design rarely comes from a single idea or a sudden moment of inspiration. Instead, it comes from a long, iterative process—observing, testing, failing, refining, and trying again. Most of the work that shapes a final design happens behind the scenes, long before anything looks polished or presentable.

Design is also not just about aesthetics. It’s about understanding materials, structure, light, textures, human behavior, and how all these elements interact over time. Many people see the final image, façade, or model, but they don’t see the countless sketches, physical mock-ups, rejected versions, and experiments that led to it.

For me, observation plays a huge role. I spend a lot of time studying small details—textures on surfaces, how light changes throughout the day, how shadows move, how people use space—and these observations slowly become design elements. A texture might evolve into a façade system; a shadow geometry might become a circulation strategy; an urban rhythm might emerge from something originally found at a small, almost invisible scale. These transformations take time, patience, and many iterations.

So if there’s one thing I hope people understand, it’s that design is a process of discovery. It’s not about finding the perfect idea right away—it’s about being open, curious, and willing to let ideas evolve through experimentation. The final design is only the tip of the iceberg; the real work, and the real beauty, lies in the journey that leads to it.

Balancing client expectations with my own ideas is one of the most important parts of the design process, and I see it as a form of collaboration rather than compromise. For me, everything begins with listening—understanding the client’s needs, their ambitions, and the deeper motivations behind what they want. Once I have a clear understanding of that foundation, I look for ways to align my design principles with their goals.

I believe that staying true to my ideas doesn’t mean being rigid—it means being clear about the values that guide my work. My approach is rooted in observation, experimentation, and a strong sense of spatial narrative. Instead of forcing my ideas onto a project, I try to show clients why certain design directions can enrich their vision. When clients can see the logic, the intention, and the possibilities behind a concept, the conversation becomes much more productive.

I also rely heavily on iterative explorations—sketches, diagrams, physical models, and visual studies—to translate abstract ideas into something clients can respond to. This helps bridge the gap between conceptual thinking and practical expectations. Through these iterations, we often discover solutions that satisfy both the client’s requirements and my design intentions.

Ultimately, I see the balance as an evolving dialogue. Good design happens when both sides bring something meaningful to the table: the client brings real-world needs, and the designer brings perspective, creativity, and expertise. When these two forces meet with openness and respect, the final result becomes stronger than either one alone.

One of the main challenges I faced while developing my award-winning thesis was the highly experimental nature of the project itself. Because the design was rooted in observing light, analyzing shadow geometries, studying textures, and translating these findings into architectural language, the process required constant testing, rebuilding, and refining.

Many of my early experiments failed—shadow patterns collapsed when scaled up, textures behaved unpredictably, and spatial ideas that appeared promising on paper often felt completely different once modeled physically. These moments forced me to pause, rethink, and challenge my assumptions.

Another challenge was the sheer amount of iteration needed to push the concept forward. The project evolved through dozens of models, material tests, and compositional studies. Each version taught me something new—how a slight shift in proportion changes the atmosphere, how light reveals unexpected geometries, or how textures can inform structural rhythms. The difficulty was learning to embrace this slow and sometimes uncertain process, rather than rushing to a final form.

What helped me overcome these challenges was persistence and my tendency to learn through observation and hands-on making. I’m someone who absorbs knowledge by studying details—how surfaces react to light, how shadows move, how patterns form naturally—and then translating those observations into design elements. This mindset allowed me to see each “failed” experiment not as a setback but as essential information.

I was also encouraged by my professor, who reminded me to trust my way of seeing the world and to design from that perspective. That support helped me stay confident and grounded even when the direction felt unclear.

In the end, the challenges became the very thing that shaped the identity of the project. They pushed me to refine my design voice, stay curious, and build a project that was honest to the way I observe, interpret, and transform the world into architecture.

When I hit a creative block, I try to step away from my desk and reconnect with activities that bring me energy. Playing tennis is one of my favorite ways to reset—moving my body, staying active, and feeling the rhythm of the game helps me clear my mind and recharge my focus. It brings me back into a more positive, energized state.

I also go hiking whenever I need deeper clarity. Being surrounded by nature helps me find calmness, and the quiet environment gives me space to think without pressure. The landscapes, light conditions, and natural formations often become unexpected sources of inspiration for my design work.

Street photography is another important way I break through creative blocks. Walking through the city and photographing details allows me to observe textures, shadows, materials, and everyday moments that people often overlook. Many of these small discoveries later become ideas for new design elements or spatial concepts.

For me, creativity returns when I move, observe, and allow my mind to wander. These activities help me reset, stay open, and rediscover inspiration in the world around me.

One of the strongest personal values I bring into my designs comes from my long-term observation of Chinese cities and the environments I’ve lived in. Over the years, I’ve watched how history, culture, and urban development have reshaped the sense of community in China.

Buildings are replaced quickly, towers grow taller, and the physical and emotional distance between people continues to widen. The traditional sense of neighborhood—something I remember vividly from my childhood—has slowly faded from the urban landscape.

Through my work, I try to reconnect with that lost sense of community. My observations of changing streets, demolished neighborhoods, and transformed public spaces have made me think deeply about how architecture can rebuild human connection. I draw from these memories and real-life experiences to explore how design can bring people closer—through shared spaces, spatial rhythms, and environments that encourage interaction rather than isolation.

This desire to rediscover and reinterpret the community spirit I grew up with is something I consciously infuse into my designs. It reminds me that architecture is not only about form or function, but also about identity, belonging, and the relationships between people and their environment.

The advice I would give to aspiring designers is to stay curious, stay observant, and stay patient with the process. Design is not about finding the perfect idea immediately—it’s about learning to see the world differently. Pay attention to small details, textures, light, and the environment around you. These observations will become your most authentic sources of inspiration.

Don’t be afraid of not having a “traditional” background. My own path into architecture was unconventional, and it taught me that passion and persistence can take you very far. What matters is the willingness to keep learning—through self-study, through experimentation, and through making mistakes.

Also, be honest with your own perspective. Your experiences, your culture, your memories, and even your struggles all shape your design voice. Embrace that uniqueness instead of trying to imitate others.

And finally, be patient. Good design takes time. Iteration, failure, rebuilding—these are not setbacks; they are essential parts of finding your own way. If you commit to the process and stay open to exploration, your work will grow naturally, and success will follow in its own time.

If I could collaborate with any designers, past or present, I would choose Louis Kahn and Alvar Aalto. Louis Kahn has always been one of the greatest architects in my mind. His work carries a timeless sense of presence, silence, and spirituality. He understood light in a way that feels almost sacred, and the spaces he created have a depth that goes far beyond function.

I would love to learn from the way he thought about material, proportion, and the emotional power of architecture. A collaboration with him would be an opportunity to explore architecture at its most profound and elemental level.

I would also choose Alvar Aalto, whose sensitivity to human experience is extraordinary. His work demonstrates a rare balance between architecture, nature, and craftsmanship. Beyond buildings, he designed furniture and everyday objects with the same care and intention. I’ve always been fascinated by furniture design, and I admire how Aalto moved seamlessly across scales—from the detail of a chair to the planning of an urban space. Working alongside him would offer a chance to understand how material, touch, and form can shape comfort and atmosphere in both intimate and large environments.

Both Kahn and Aalto approached design with honesty, humanity, and depth—qualities I deeply aspire to. Collaborating with them would mean learning not just how to design, but how to think.

One question I wish people would ask me is: “What do you hope to express or recover through your work?”

My answer is that I am constantly trying to reconnect with the sense of community that once existed in the Chinese cities I grew up in. Through long-term observation of my surroundings—both in China and abroad—I’ve seen how rapid development, high-rise construction, and the fast replacement of buildings have gradually pushed people farther apart. The neighborhood spirit I remember from my childhood—the warmth, closeness, and everyday interactions—has slowly disappeared from the urban landscape.

In my work, I try to use design as a way to rebuild that sense of connection. I often think of a verse by Su Shi: “If only I could have thousands of mansions, to shelter all the poor and needy and bring them joy (安得广厦千万间,大庇天下寒士俱欢颜).” It expresses a longing to create spaces that shelter, comfort, and uplift people. In my own way, I hope my designs can offer warm, beautiful, and safe environments—whether indoors or outdoors—where people can feel protected and invited to connect with one another.

I translate this intention into architectural elements: studying textures, observing light, shaping circulation, and designing spatial rhythms that bring people closer rather than isolate them. I explore how a single detail, a gesture of light, or a thoughtfully shaped space can influence how people interact.

So the question I wish people would ask is not about form or aesthetic preference, but about intention: “What human value are you trying to rebuild through design?” Because for me, architecture is ultimately about creating spaces that nurture community, belonging, and human warmth.

Winning Entry

ADVERTISEMENT

IAA GLOBAL AWARDS

MUSE Awards

Vega Awards

NYX Awards

TITAN Awards

- TITAN Business Awards

- TITAN American Business Awards

- TITAN Property Awards

- TITAN Women In Business Awards

- TITAN Health Awards

- TITAN Innovation Awards

- TITAN Brand Awards